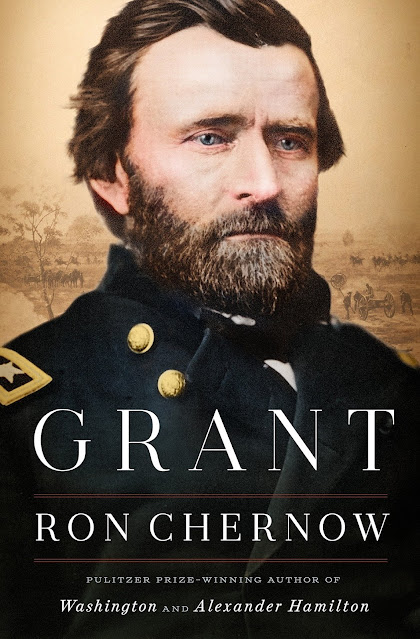

In today’s nonfiction review, we’re talking about General,

and President Ulysses S. Grant, in Ron Chernow’s biography “Grant.” Ulysses S.

Grant may have had his problems when he resided in the white house—because he

wasn’t a natural-born politician—but due to the sum total of his life, he’s

become my favorite historical American President.

I love how comprehensive Chernow is with this biography. He gives us warts and all of Ulysses S. Grant, what made him a great leader, and what his blind spots were. Grant was an incredibly honorable man who always sought to do what he promised and intended to do and couldn’t conceive that the people closest to him wouldn’t necessarily give the same effort. Chernow highlights that this was even a problem during Grant’s incredible military career during the Civil war, but it was a veritable Achilles heel during his presidency.

It was fascinating to discover how Grant thought and what his skills and weaknesses were in life, and even more so than his own memoirs, I feel like “Grant,” the biography is the closest thing we can get to reading his mind. General Sherman put it best that Grant was a unique intermingling of strength and weakness and that he was a mystery—even to himself.

This is a biography from birth to death which gives us a complete picture of the subject. A thing I loved about the man—that Chernow’s biography taught me—is that Grant had experienced failure multiple times in his life but constantly reinvented himself to meet the current challenges of his life. He started as a shy boy who loved horses who would one day rise to the highest possible military rank, and hero of the republic, then President of the United States, a world traveler, and finally, a best-selling author posthumously.

The quality that General Grant possessed that I think I admire the most about him—and I feel is lacking in politicians today—was his ability to recognize when he was wrong and change his mind about things. He was the son of an abolitionist, but as a young man, he was noncommittal on the subject of abolishing slavery. He even once owned a slave, given to him by his father-in-law. But, over the course of his life, he freed his one slave, and during his military career and as President, he evolved as a person and became an ardent defender of equal rights. Grant, as President, even uncharacteristically passionately railed against southern atrocities where black men and women were murdered in orgiastic periodic paroxysms of death, sanctioned tacitly by southern officials.

What I don’t love about this book:

As a biography, “Grant” is amazing, and there isn’t much I can talk about that I didn’t like about it. It can be accused of being a bit long, but I forgive that because the subject matter is so interesting to me. My old nemesis of super-long chapters raises its head in this book, but I get why Chernow wrote them this way.

Mainly, I can talk about what I didn’t like about the subject of the biography, General Grant himself. Ulysses S. Grant became a personal hero of mine as I read this biography and his own memoirs, and it always hurts the most when your heroes fail to live up to your expectations, falter, and show their human failings. I’m not one to attack Grant for his drinking problem—and he was undoubtedly an alcoholic—many a “lost causer” have already beat that point to death, and I don’t respect them as people or historians. The two things that hurt the most for me were reading about General Order No. 11—a frankly racist order that is ironic when you consider the war’s aims—that targeted exclusively Jewish people, and how Grant wasn’t there for John Rawlins when he died. It broke my heart how after Rawlins served Grant so faithfully during the war, and how important loyalty was to Grant, that he barely mentioned him in his memoirs and when Rawlins lay dying, Sherman had to lie to him, telling him Grant would be there soon—just five more minutes—when he knew Grant couldn’t possibly make the journey in time.

I know I said above that I like complete biographies—but one of the terrible side effects of reading one is that when you find yourself genuinely admiring the person the biography is about, you start dreading the end. After all, the hero always dies at the end of a biography of their entire life. At several points in the last third of the book, I started slowing down because I knew from other sources than this book, primarily from a docudrama of the same name, that the end of Grant’s life was awful. Despite being the hero of the union—the man in the field who ultimately made it possible to save America—Grant died nearly destitute, writing his memoirs while dying in agony from throat cancer to save his family from poverty.

This preview is an Amazon Affiliate link;

as an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.

Author's Website: https://ronchernow.com/

Parting thoughts:

This book reminded me that we have a long, shameful history of forgetting our heroes here in America. As you might imagine from above, I’m not too keen on “the lost cause” historical theory of the American Civil war, which recasts General Lee as a hero and General Grant as a bumbling idiot and butcher.

I’m also currently reading a biography of J. Robert Oppenheimer. Again, we let something like McCarthyism destroy a man who—for better or worse—changed the course of human destiny, giving us the ability to control nuclear power.

On a far less controversial note than the father of the atomic bomb, the first responders of nine-eleven didn’t get a guarantee from these United States that their healthcare would be paid for in perpetuity until 2019. Nine-Eleven happened in 2001, by the way. We thanked them for their courage and bravery during the worst terrorist attack in modern American history, and then—for nearly twenty years after—we started hem hawing away about cost. In the wealthiest country in the world, as our literal living heroes began dying of cancer which tore their lungs and other organs apart—cancer they got saving lives in the ruins of the twin towers—congress wanted to have a serious discussion about nickels and dimes.

Even after they had to be shamed into doing the right thing as a group, two senators, Mike Lee of Utah and Rand Paul of Kentucky, still voted against it. Literally and unequivocally stating that dollars are more important than human lives—even heroes. Mitch McConnell, also from Kentucky, who I do not like for numerous reasons, wasn’t even so callous as that. Both Lee and Paul claim to be upstanding members of the party of Lincoln and Grant—and oh—how far the GOP has come.

No comments:

Post a Comment